Rush Roberts was born November 30, 1859. A family history prepared by George Roberts named the father as “Latakutskalahar (Fancy Eagle),” and the mother “Chiha (Reed Matting).” These names are Riítahkaackarahaaru, Proud Eagle, and Chihiítu, Reed Mat. Both Proud Eagle and Reed Mat died “in the land of Nebraska” – Proud Eagle was killed “by enemy Indians.” Late in life Rush Roberts responded to a list of questions received from a researcher, and he mentioned his father: “My father was a Doctor; he died when I was about four years of age. My stepfather was a hunter and trapper.” This suggests that Proud Eagle was killed about 1864, and Reed Mat married another Skidi man. This genealogy traces the Roberts family history back to the late 18th century. But in 1977 Garland Blaine took issue with certain aspects of this family heritage, and he said that Rush Roberts was “a mixed blood.” Then in 1983 I heard a very different story. In July that year I sat down with my uncle John Knife Chief to go over a list of Pawnee men who had signed the Agreement of 1892 – the generation that adopted the formal use of inherited surnames. When we got to the name “Rush Roberts,” Uncle John paused. He said Rush’s real parents were, as he put it, white immigrants. They might have been German, he said. One day they were both killed by the Sioux. A Skidi group came upon the slaughter and they found a living child and Rush grew up as a Skidi. These stories are confusing. Was Rush Roberts the scion of Skidi lineages? Was he a “mixed blood”? Was he an adopted son of Proud Eagle and Reed Mat? We can say for sure that he grew up as a member of a Skidi family, and he shared with his son Henry his memory of his Skidi father, Proud Eagle, who was married to Reed Mat, his mother. Henry wrote in a 1903 school essay, “He said that when he was young his father was killed in a battle with the Sioux Indians, and so he did not get to see his father very long.” Perhaps we can reconstruct an arguable model of what happened. At the killing of his birth-parents, Rush was likely an infant, too young to retain any memories of what had happened. And he was still quite young when his first Skidi adoptive father, Proud Eagle, died at the hands of the Sioux. Pawneeland in those days was an embattled realm. The colonizing Sioux and their client states and allies wrested away swathes of Pawnee hunting grounds by military invasion, taking control of steadily declining herds of buffalo. And they assaulted the Pawnees in their last city, Wild Licorice Creek – an earthlodge metropolis founded in 1859, a few months before the birth of Rush Roberts. That city had two Skidi suburbs, and in later life Rush said, “The village I lived in had about fifty lodges in Nebraska.” From its founding, Wild Licorice Creek was a city under siege. A New York Times report described a Sioux attack on the “Scheedees” in May 1860 and “a sharp fight took place, lasting about half an hour in which three Pawnees were killed and four severely wounded,” with honorable mention of the deeds of Baptiste Bayhylle and Crooked Hand. Historian Mark van de Logt noted that “between April and September 1860, Sioux raiders struck the town no fewer than eight times.” Clyde Milner added: “In the summer of 1860, even with a company of US soldiers on the reservation, the Sioux destroyed sixty Pawnee lodges. Early in 1861, with the Pawnees off in their winter camps, the Sioux virtually occupied the reservation. That fall they burned the prairies to prevent a successful Pawnee hunt, and by January many Pawnees had no food.” The Pawnees also observed Sioux attacks on their American neighbors. In early September 1862 the American farmer for the Pawnees reported that the Sioux had “killed a white man a few miles above” the Pawnee city. And “they were intending to have a big fight with the Pawnees.” He heard “that the Sioux were in large bodies, of 500 each, at various distances on all sides of the Pawnee village.” Historian George Hyde touched on events in the summer of 1863: “The Sioux were very troublesome this summer. They started with a big raid on June 22, when they charged straight into the Pawnee villages, killing and scalping some Indian women, with Agent Lushbaugh and the officers of the cavalry company which was supposed to be on guard looking on. Later in the summer 300 Brulés made an attack on the Pawnee villages, wounding the captain of the cavalry company with an arrow and killing one soldier and a number of Pawnees before the Indians and cavalry could mount and drive them off. The cavalry company seemed useless, small parties of Sioux getting in almost daily to kill Pawnee women in the corn patches and to enter the Indian villages at night to steal horses.” Surveying this history, it is certainly possible that Rush Roberts was the son of non-Pawnee parents killed by the Sioux somewhere in Pawneeland – parents who might well have been immigrants from Germany. Their infant son survived. The little boy was too young to retain any memories of those grim events. And Proud Eagle and Reed Mat took in the orphan and they named him Arikaraaru. The name means “horned one” and it refers to a “stag, buck deer.” Perhaps we could translate it as Deer Antlers. In later years he could vaguely recall how his Skidi father died at the hands of an invading Sioux military expedition – a dim memory reinforced by things his mother said in his childhood before she died. Other Skidis in the community knew the truth, and perhaps some Pawnees thought Deer Antlers was a Skidi with American ancestry. Deer Antlers became a youth in this time of war, and one summer day in 1873 he survived the genocidal Sioux slaughter of Pawnees at Massacre Canyon. An American named Royal Buck visited the scene. He published a somber report in a local newspaper: “It was indeed a regular massacre… for nearly four miles down the canyon the dead bodies are still lying bleaching in the sun or putrifying in the water or slough holes… near one hundred victims are lying on the ground and full two thirds are squaws and pappooses. All or nearly all are scalped.” In 1876 Deer Antlers joined the final enlistment of Pawnee Scouts. Mark van de Logt quoted Rush in his 2010 book on the Pawnee Scouts: “The Sioux and Cheyennes were our enemies, and I had this chance to operate against them.” It appears that Deer Antlers was present at the Dull Knife battle in late November 1876. He recalled, “About three days after the Cheyenne battle we had the name changing ceremony at our supply wagon camp.” Perhaps this was the occasion when Deer Antlers took his Skidi father’s name, Riítahkaackarahaaru. The name is typically translated as Fancy Eagle, but the word karahaar means “be neat, fastidious, particular, as in one’s dress or work; be proud.” The term pertains to a person who takes pride in being meticulous and “proudly attired.” And riítahkaac refers to a golden eagle. Douglas Parks translated this name as Proud Eagle. And it must have been during the 1880s when Proud Eagle took another name, borrowing an American name “Rush Roberts” from a Quaker official of the Board of Indian Commissioners. In October 1875 Benjamin Rush Roberts had visited Pawneeland in Oklahoma, and he was struck at how this new Pawnee realm looked quite beautiful “in the light of the setting sun… a picture which no pen could adequately describe.” And in 1904 when George Dorsey and James R. Murie published Traditions of the Skidi Pawnee, they included one narrative told by “Fancy Eagle.” And “God-of-Wind” tells of a “wonderful boy” who could perform magic, transforming a clay buffalo “into a live buffalo calf.” Stitakäu or Womb “could call the buffalo” and “he seemed to make the ground open so that buffalo came forth.” This narrative has the feel of an old tradition handed down for generations – it ends with Stitakäu becoming a divinity in the north: “Hikusu, Breath or Wind.” And the people made offerings in those days, as the story told. And Stitakäu became Hikusu “and the people knew that he did not die”; and still, he is “living and stands in the north…” And the infant boy became Arikaraaru. And he became Riítahkaackarahaaru. And one day he became Rush Roberts. And he lived to a great age – he grew very old in Pawneeland, a beautiful realm “in the light of the setting sun… which no pen could adequately describe.”

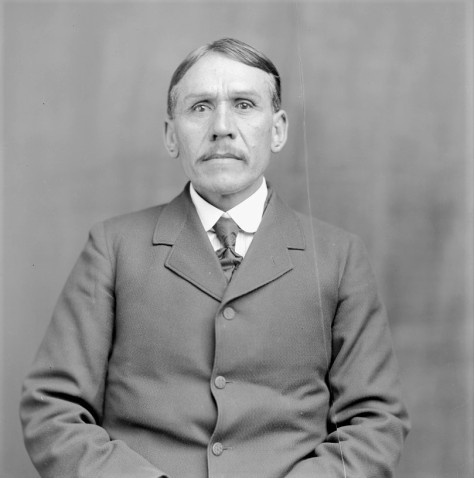

Photo by Thomas Smillie: “Ray-Tah-Cots-Tey-Sah-Ru, Fancy Eagle, called Rush Roberts,” January 21, 1905