Envisioning how I am connected to the past, I sort through the forever unfolding historical geography that has shaped my immediate world. I focus on various inner pathways that give me a sense of depth as a person – a shifting map of identities and moments and life-narratives. But many trajectories of history have shaped me, including things that I don’t often ponder. One such arc of definition has to do with the invasion of Pawneeland. To sort out what I think this means, it seems useful to examine a somewhat mysterious incident that happened long ago.

During the early 1840s an American trader set down a memoir of his travels. Josiah Gregg had “crossed and recrossed the Great Plains four times” from 1831 to 1840, and on his first journey he heard a story about the Pawnees. Arriving at a small eminence called Pawnee Rock, he learned it was so named after a battle that had been fought there “between the Pawnees and some other tribe.” Gregg didn’t set down any detail, but it was a story that had some currency in those days.

In August 1835 the diary of an American dragoon named Lemuel Ford made brief mention of “a noted Rock Sandy called Pawney rock[.]” And in September 1843 another dragoon named Philip Cooke found himself at Pawnee Rock – he knew something about its history, reporting a rumored battle there in which the Pawnees had fought “Camanche hordes.” He told a dramatic tale of how “a small party of Pawnees” took refuge on the “rocky mound” and suffered there from thirst and finally charged to a “heroic death…” This tale, he said, explained how the “rocky mound” got its name.

Lewis Garrard visited Pawnee Rock in the fall of 1846. He said nothing about the Pawnees, but he did find “a point of friable sandstone jutting out from the rising ground… thirty-five or forty feet in height…” The landmark today is a humble remnant of the original hill that these American travelers saw – during the 1870s the Americans began to mine the jutting rocky hill for construction materials.

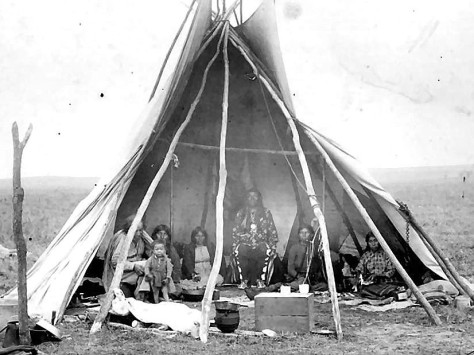

Pawnee Rock circa 1870s, JR Riddle

The Pawnee story accounting for the name of the hill faded from American memory. But the tale did not die away in Pawneeland. Sometime during the 1860s / 1870s two American brothers heard very similar narratives about Pawnee Buttes in Colorado and Courthouse Rock in Nebraska. These brothers spoke Pawnee, and we can assume that they heard their accounts from unidentified Pawnee storytellers.

A memoir of the life of Frank North told of a “running fight” between a Pawnee war expedition and the Sioux during the 1850s. The Pawnees ultimately took refuge on a butte in Colorado that was “almost perpendicular on all sides except one,” and there they suffered from thirst and hunger. But one night they tied their lariats together and slipped away in the dark. Ever after, the area became known as Pawnee Buttes.

Frank’s brother Luther was also aware of the Pawnee Buttes story, and he visited Courthouse Rock in January 1877 with some Pawnee Scouts. He mentioned hearing an account about Courthouse Rock similar to the Pawnee Buttes narrative: “…a story of a war party of Pawnees that was driven up there by the Sioux, and after having been kept there for several days escaped down the cliff by tying their ropes together and sliding down.” He felt doubtful about both accounts, picturing light-weight Pawnee “hair ropes.” He also wondered why the Pawnees could not name anyone involved in the incident or incidents.

Ten years later George Bird Grinnell visited Pawneeland in Oklahoma and he heard the Courthouse Rock version. He wrote that “a war party of Skidi” had camped near Courthouse Rock and they were driven to the hill by the Sioux. There was only one way up to the top, and the Sioux stood guard and the Skidi men “suffered terribly from hunger… and thirst.” The leader prayed and “something” told him to seek a place to climb down. He carved a notch in a “soft clay rock” and the men tied their lariats together and escaped.

Grinnell was also aware of the Pawnee Buttes version – he later edited Frank North’s biography and he became aware of Luther North’s skepticism about the stories. Pawnee men carried two kinds of ropes, said Grinnell, and the rawhide type could have sufficed to bear the weight of escaping men. And considering the attributed locales of Courthouse Rock and Pawnee Buttes, he thought that similar incidents could “have happened more than once.”

The Pawnee scholar, James R. Murie, set down what can be taken as the most authoritative account of the hilltop siege. He heard an account told by an old Pawnee priest named Roaming Scout, and George Dorsey published it in Traditions of the Skidi Pawnee (1904) as “The Moon Medicine.” In choosing this title for the story, Murie and Dorsey translated the Pawnee term waruksti as “medicine.” But this Pawnee term refers to a range of more esoteric ideas like holy, full of wonder, mysterious. In the present circumstance, a more supernatural context is arguable, as with the term “magic.”

In Roaming Scout’s narrative, a Skidi man called Taihipirus had been blessed by Spider Woman as a youth, and he had grown up with “womanish ways.” Becoming respected as a war leader, he took an expedition into the south of Pawneeland and there they were driven onto Pawnee Rock by a vast coalition of “ten or eleven tribes” who encamped around the hill.

It is convenient to refer to this tradition as a war story, but only one Pawnee died in the incident. A “little fellow” who was an errand man “rose up and ran down the hill” and was captured and executed. In the course of the siege two Skidis slipped down the pathway and met some Cheyennes who had a ceremonial kinship with the Pawnees, and they arranged for the two men to shake hands with the leaders of the other tribes. But this friendly gesture did not resolve the situation.

The Skidis endured great thirst, and one night Taihipirus received a vision from Spider Woman. He watched her come down her rope from the moon, and she told him about a “great rock” that could be moved to one of the sheer edges of the hill. Following Spider Woman’s instructions, Taihipirus and his companions escaped by tying together their ropes and attaching them to the stone.

From the various extant accounts, it is evident that by the 1830s a Pawnee story about a war expedition and Pawnee Rock was widely known among Americans in the central Plains. The reports by Josiah Gregg and Philip Cooke do not contain much detail, but they refer to an incident that happened sometime before circa 1831. The stories must have originated from Pawnee storytellers, spreading to fur traders and American officials who had dealings in Pawneeland.

By the 1870s a similar story about Pawnee Buttes and Courthouse Rock had appeared, reported by the North brothers. George Bird Grinnell in 1889 and James Murie in 1904 both published more detailed stories. Grinnell did not specify his source and did not name any Pawnee participant, but he said the Pawnee party was Skidi. The Murie / Dorsey narrative came from Roaming Scout, a Skidi man who was born about 1839. He identified the war expedition as a Skidi group and its leader as Taihipirus, and he associated the incident with Pawnee Rock.

The similarities among these various narratives tend to suggest some form of diffusion of an original story into divergent variations. Both Luther North and Grinnell knew of more than one version, and they disagreed about how to interpret the tales. But given the chronology of known accounts, we can surmise that the Pawnee Rock story described the original event, and it happened sometime before circa 1831.

Beyond the obvious similarities, another slight clue in the Frank North story hints at diffusion of the story. The Murie story about Taihipirus tells of the influence of Spider Woman. None of the other accounts mention that element, but the Frank North story says that after the Pawnees escaped from Pawnee Buttes, a spring-fed stream emerged from the butte, “and the Pawnees claim that there was no stream there at the time they were besieged…” As Murie explained in a note in Traditions of the Skidi Pawnee (p. 335), Spider Women “inhabited the sides of mountains, where they stayed with their legs far apart, and were the source of springs which furnished sweet water.” The mention of a new spring at Pawnee Buttes could be taken as a veiled reference to Spider Woman.

Why would a Pawnee war story become more a matter of myth than history? It isn’t certain that this is the case – we can’t entirely rule out the possibility of multiple similar events occurring at three different locations over time. But the basic structure of the tale could easily have lent itself to mythologizing processes, and that seems to be what happened. Between about 1830 and 1870, the invading Sioux and their allies engulfed the Pawnee homeland, wresting away control of large swathes of territory at the periphery of the realm – the lands that contained Pawnee Rock, Pawnee Buttes, and Courthouse Rock.

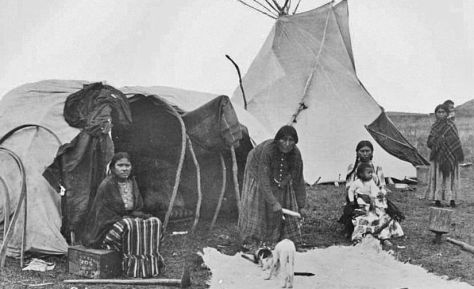

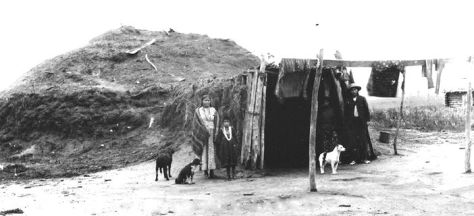

The originating incident at Pawnee Rock must have occurred in the years before the Sioux colonization of Pawneeland. During the decades that followed, the encroaching Sioux empire and their many allies surrounded the Pawnee realm, and this invasion was not merely a slow demographic shift. It was not merely a gradual interplay of complex interactions marked by occasional rivalry. It took the form of a brutal war driven by genocidal colonialism. Pawnee families were slaughtered in their cities, in their hunting camps.

The Pawnees resisted the invasion. The Pawnee bands unified; they took refuge in consolidated cities and they finally forged a military alliance with the United States. And at last during the 1870s they escaped to Oklahoma Indian Territory. There the Pawnee people continued to slide down an implacable demographic decline, devastated by epidemics and economic collapse. But in the end, Pawneeland endured. Remnants of the Pawnee Confederacy survived.

Through those years the Pawnee Rock story underwent a transformation, diffusing from Pawnee Rock to Pawnee Buttes and Courthouse Rock. In this story, a retreating embattled group sought refuge in the midst of a sea of enemies, and they escaped safely. This eventually gave rise to a crescent of narratives across the old Pawnee homeland, tales of resistance dimly lit by the wonder of the Moon, visions of Spider Woman. By the end of the century, the extant versions of the story roughly approximated the map of Pawneeland that had been overwhelmed by Sioux colonialism.

The tradition of Taihipurus and Pawnee Rock ultimately memorialized the enduring Pawnee struggle for survival. The making of a mythologized geography served to refine the telling of this history into storytelling. Relating versions of this story, the Pawnee people could feel optimism about the challenge to preserve what it meant to be Pawnee in an embattled world. That world ultimately gave rise to the world in which I was born.

But the tale does not end there. It has recently become evident that sometime around 1960 the legend of Pawnee Rock took an unexpected turn. With the release in 2007 of JRR Tolkien’s The Children of Húrin, I realized that he drew on this particular war story of Pawneeland to colorize a fantasy battleground of Middle-earth – the story of Mîm the Dwarf and his hilltop refuge. With this development, the Pawnee memoir of Taihipirus and the Moon Magic has found new momentum in the world. When we observe the journey of this tale of wonder and vision and mystery, we glimpse a slow transformation of a moment of history into myth.

My related Tolkienland essay: “Mîm and the Moon Medicine”

My related essay at The Wandering Company: “The Spider’s Springs”