In late August 1914 two Skidi Pawnee men appeared in Lincoln, Nebraska. They had been invited to tour Pawneeland with Melvin Gilmore, a scholar at the Nebraska State Historical Society, and Leonard Herron (editor of a weekly newspaper) and his wife. One of the Skidis was an elderly Leader named White Eagle; the other was Charles Knife Chief, a younger man who, unlike White Eagle, had a good grasp of English.

This was the deep end of summer, full of hot sunny days. The five travelers set forth into the bright countryside, riding in Herron’s new “five-passenger” Model T, trekking down roads that have since become paved and convenient. White Eagle and Knife Chief murmured in Pawnee, and Knife Chief passed along various comments to Gilmore, who later prepared a memoir of the journey.

The party stopped at a farm near Fullerton, Nebraska. Walking out into a field of wheat, White Eagle spoke of a Skidi town that had long ago stood there. He called it “Kitkehak Pako (Ancient Village).” But now it was 1914 and a man named CP Cunningham owned the property, and every spring he plowed the ground and planted crops there.

Gilmore’s account of the visit is touching. White Eagle walked over the field and stood on the shore of the Many Wild Potatoes River (now called the Loup River), gazing over flowing waters, and he pointed out into the current. Knife Chief translated his comment: “My father’s house, where I was born, was there.” White Eagle then gestured toward “the higher hills” behind the house and he spoke of a Skidi ritual that had occurred there – the Morning Star Ceremony and the killing of a young captive girl.

By 1914 the field had doubtless been plowed many times, erasing traces of slowly disintegrating earthlodge rings and other features. Gilmore wrote that it was “easy to see all over the site and to see all the contour.” But if any fading earthlodge circles were still visible in the wheat or at the riverside, Gilmore made no mention of that in his manuscript.

When NSHS archaeologists visited the site in 1940, they found no evident earthlodge rings or other surface features. They surmised that the entire city had eroded into the river. On nearby hilltops they excavated two earthlodge floors attributed to “an Upper Republican Aspect site” dating back some centuries – ancestral to the Pawnees and related communities. And they located what seemed more recent features: two post molds, a burned area, and a few fragments of Pawnee pottery. Thinking of White Eagle’s report of a ritual sacrifice here, they wondered whether they had found evidence of a Morning Star Ceremony.

Cedars stand at the location identified in 1940 as a possible Skidi Morning Star Ceremony site; photo taken October 2015

White Eagle died in 1923. He is today revered by many Pawnees as a respected ancestor, a hereditary Skidi Leader. It is also apparent that he spoke to his kin about his 1914 visit to Pawneeland, recalling his pleasure at visiting the vanished Skidi town where he had been born.

Garland Blaine was a grandson of White Eagle’s brother, John Box, and he visited the Cunningham site in 1976. There Blaine was given a note that came from the hand of a daughter of CP Cunningham. She recalled how White Eagle had said “that the village on the high bank was his fondest memory.” White Eagle felt moved to find himself gazing back to his earliest memories of Pawneeland, the city where he had been born.

Available records pertaining to the birth of White Eagle are extensive and unclear. The earliest record is his Pawnee Scout 1864-1865 enlistment, indicating his birth about 1837. White Eagle traveled to Europe in 1874, and as reported by researcher Dan Jibréus, two advertisements list his age as 23 and 28. But these must be spurious. It does not seem at all likely that White Eagle was born in 1851 or 1846. Pawnee Agency allotment records give his age in 1892 as 56, born about 1836. In an 1895 affidavit White Eagle said he was “60 years of age…” born circa 1835. A 1903 census of Pawnees recorded his birth at “about 1836.” These records from 1864 to 1903 establish his birth at circa 1836.

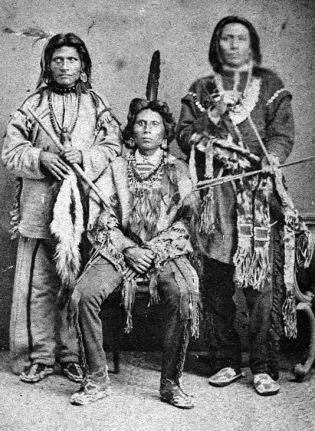

Red Fox, White Fox, and White Eagle in Sweden 1874

But just a few years later White Eagle settled on an older date of birth. In a 1913 transcript of Pawnee Council Minutes, he said, “I am 82 years old” – circa 1831. The next year at two heirship hearings in June and early August 1914, he testified that he was age 83. Later that same August, Gilmore wrote that White Eagle “is now far advanced in age, being about eighty-five years old.” That would place his birth around 1829. I have seen an undated family tradition (an unsigned typescript dating to the 1970s) asserting that White Eagle was “born in Nebraska about the year 1825.” And drawing on Garland Blaine’s family traditions, Martha Blaine wrote that White Eagle was born in 1831.

These records are a little confusing. We can say with certainty that White Eagle was born sometime between 1829 and 1837. It is evident that during the last decade of his life, White Eagle came to believe that he was born about 1831, but records stretching over four decades agree that he was born circa 1836. This can be taken as the most trustworthy date.

With this likely date in hand, as well as his account of being born at the Cunningham site, we should look for evidence of a Skidi earthlodge community at that location around 1836. Skimming various records, I can find no hint of such a town. Instead, I get the impression that up to 1842 all the Skidi bands dwelt together in one city known today as the Palmer site. This site can be identified with some confidence as the “Old Town” of Skidi tradition.

In April 1835 missionary John Dunbar visited the Skidi city on the Many Wild Potatoes River and he noted, “The Loup village is quite ancient.” This was no doubt a reference to the Skidi name for the city: Kitkahahpakutu, Old Town. In September 1839 Dunbar conducted a survey of Pawnee communities and he prepared a hand-drawn map that showed a single “Loup village” of “64 lodges” on the Many Wild Potatoes River. This was the westernmost Pawnee community, no doubt the Palmer site city.

If there was a Skidi Pawnee earthlodge town at the site of the Cunningham farm during the 1830s, we would expect to find some mention of it. As far as I know, the 1914 Gilmore account is the only record of it. Given this circumstance, we must ponder whether some kind of error accounts for White Eagle’s information.

I have no idea how the Cunningham farm was selected as a place to visit in 1914. One possibility is that White Eagle gave detailed instructions from memory and the travelers found themselves knocking on CP Cunningham’s door. A news report from a Columbus, Nebraska newspaper seems to indicate that White Eagle was indeed thinking about Old Town when the tour began. But it seems unlikely that White Eagle would have guided Herron and Gilmore to the Cunningham farm.

We can guess that Gilmore and Herron selected the site. In 1914 the archaeological study of Pawneeland was in a rudimentary state, but a good number of Pawnee sites were known, and we can suppose that Gilmore and Herron used that information to organize an itinerary for the road trip. Herron was editor of The Nebraska Farmer, and would have been well-known in the countryside, a welcome visitor – and he might have heard of various farms in Nebraska where one could find scattered artifacts. But we don’t know how the Cunningham farm was chosen.

We can speculate that when the party stopped at the Cunningham farm, Gilmore told White Eagle and Charles Knife Chief that they were standing at the location of a Skidi town. There is no record that the visitors observed any traces of an old vanishing Pawnee city in the wheat field or at the river’s edge. If nothing could be seen, it would have been reasonable for White Eagle to conclude that the river had washed everything away. Gilmore wrote that the old man “pointed to a place about two hundred feet or more in the stream” as the location of the earthlodge where he was born.

In brief, White Eagle thought he was standing at the site of Kitkahahpakutu, Old Town. Studying Gilmore’s record of that day, it does not appear that the group made any visit to the actual location of Old Town at the Palmer site. This was because Gilmore and Herron did not know about the Palmer site.

Waldo Wedel in 1936 noted that the Palmer site “was discovered by Mr. A.T. Hill… in 1922, and has been identified by him as the probable site of the Skidi village reported by Major Sibley in 1811…” Hill and his wife drew a map of what they found at Old Town in April 1922. It showed about twenty remnant ruins of earthlodges, with the rest of the city plowed away under wheat.

Old Town at the Palmer site, vanished in a corn field, October 2015

Pawnee oral tradition records the location of Kitkahahpakutu. In a narrative recorded in 1906 by James R. Murie, a Skidi priest named Roaming Scout told a story about the origin of a fraternal society, saying, “This story originated from our people when they had their village at the old village site in Nebraska about fifteen or twenty miles west of Fullerton. Kitkahapahuk, old village; that is where I was born.” The various records of his age indicate that he was born between 1839 and 1846, but the earliest records (and the majority) settle on 1839. This date is consistent with the known Skidi occupation of Old Town at the Palmer site.

We know that the Skidi bands left a city at the Palmer site in 1842, and this was called Old Town, and White Eagle was born about 1836 at Old Town. When his family left that city in 1842, he was about age 6 or 7. If all these references really pertain to the Palmer site rather than the Cunningham farm, this means that when White Eagle pictured the city of his birth, he had to summon memories from his boyhood.

The evidence is slim for a Skidi town at the Cunningham site. White Eagle did his best to fit his memories into CP Cunningham’s wheat field that day in 1914, but we should feel doubt about what happened. We can guess that had he been taken to the Palmer site, he would have said there what he said at the Cunningham farm, telling of his birth, estimating the location of his father’s house, and reporting on how a Morning Star Ceremony had been held on the ridge overlooking the city.

White Eagle was born about 1836 at Old Town on the Many Wild Potatoes River. His father was Kuh-coo-tu and his mother Chay-tah-he-kee-wah-la-wah-hiss. His younger sister (she later in life took the name Julia Troth) was also born at Old Town, just a year or so before the Skidi moved away to build a new city farther down the Many Wild Potatoes River. Two more siblings followed: Red Fox (John Box) and Cho-pee-de-cah.

At Old Town White Eagle’s mother had six siblings and his father had two brothers, so they had a lot of close relatives and extended family living in the city. And they were Skidi royalty, priests and leaders and keepers of religious bundles and ceremonies – aristocrats of the Skidi confederacy in Pawneeland. That shaped the social world of White Eagle’s childhood.

When the people gathered in their city and in their camps, they told stories. White Eagle used to talk about something his mother had seen – the time at Old Town when the stars fell. That happened in the fall of 1833. And late in his life White Eagle shared with James Murie and George Dorsey some of the stories he had heard in the course of his life. These appeared in collections of Pawnee narratives published in 1904 and 1906.

I find one story particularly interesting because it concerns “a little boy” who visited a town where a witch dwelt. That little boy “came to the village” and the witch “sent a challenge to the boy” – a challenge to dive into some nearby waters. The boy agreed and when he dove he “turned into a beaver, and went to the beavers’ den.” At last he emerged, and he shouted with the people and they killed the witch.

This was just one account of what happened. Maybe it wasn’t true; other people told a different version. They told of how the witch challenged the boy “to slide with her on the ice.” When he threw himself onto the frozen waters “there stood a big otter.” The magic otter glided on the ice “like an arrow” and the people charged and they killed the witch. Perhaps this is what really happened.

I wonder as I read this brief wisp of a story. When White Eagle narrated it long ago, did it hold personal resonations for him? He had long ago lived in a Skidi city in Pawneeland, a fabled metropolis on the shore of the Many Wild Potatoes River, an earthlodge city that slowly faded. There he became a little boy. And he heard the people tell their stories, and when he grew up he treasured those memories.

The events of White Eagle’s life… the cities where he dwelt… the stories he heard… our lives always fade, become misty and mostly forgotten. Time plows over the details. But it is almost a century since White Eagle died, and traces of his world still linger in Pawneeland. He has descendants; there are descendants of his brother and one of his sisters.

Pausing to think of people who lived long ago, and the stories they told to one another, and the cities they built and abandoned, maybe it isn’t always very easy to sort out what happened. But when we dive into those ancient waters, perhaps the past doesn’t really vanish. Maybe the past helps us to imagine the mysterious ways we keep becoming ourselves until the end of our lives, becoming many unexpected things – even sometimes becoming magical creatures of the unknowable future.

Charles Knife Chief, Melvin Gilmore, White Eagle, 1914, courtesy of the Nebraska State Historical Society